It has been over a year since one of the most bizarre freak accidents to capture the world’s attention. I am, of course, speaking of the Titan submersible, operated by the company Oceangate. The company had been operating the submersible for a few years, and it had already gone through a hull replacement, with the previous carbon fiber hull being replaced due to concerns over fatigue. This should tell you something, because most submersibles use materials with a great enough factor of safety and high enough confidence that dangerous levels of material fatigue are just not an issue.

At the time this happened, I, personally, knew very little about the operation. I had heard of a new private venture, which had been taking paying customers to the titanic. To be perfectly honest, that kind of thing isn’t all that interesting to me. Of all the shipwrecks in the world, few have been more thoroughly documented or more constantly bombarded by tourists and other activity. Sure, it still holds some level of scientific and historical interest. It is, after all, one of few liners of the era that still exists in any form. The only others that are still around are also sunk, such as the Britannic and Lusitania.

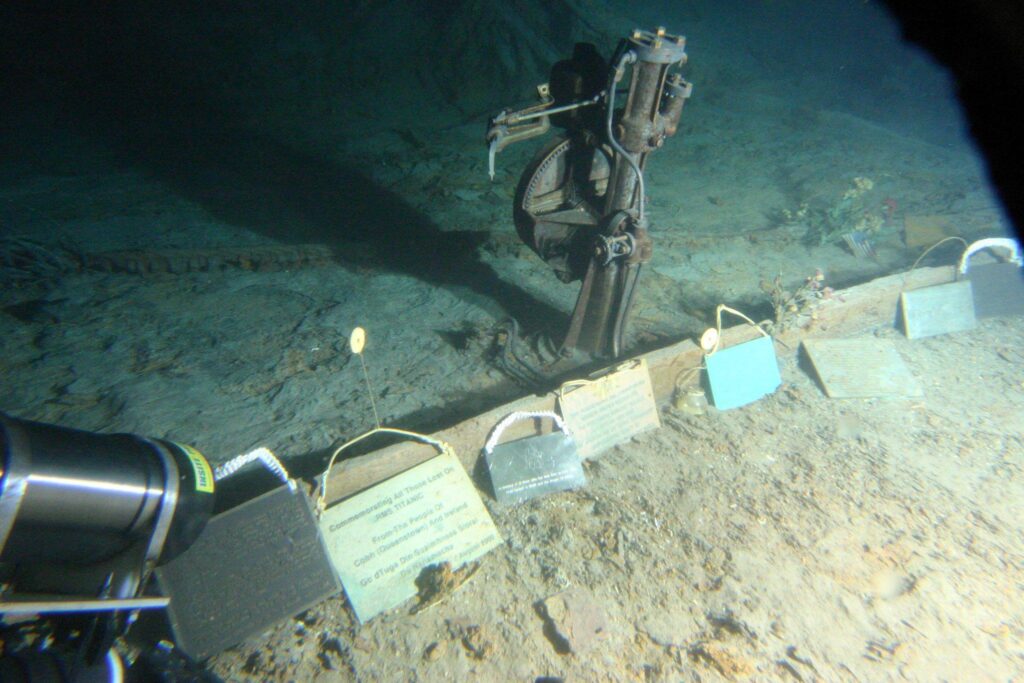

It would be one thing to lay a single plaque on the Titanic as a tribute to the tragedy, but it seems every single expedition feels the need to leave their mark and explain why they are the best and most poetic at memorializing the ship. At some point, it starts to look like litter.

A Long History Of Corners Cut:

It was not until after the catastrophic implosion of the Titan that the public at large become aware of the long history of cutting corners, skirting regulations, and doing everything to dodge legitimate criticism. Numerous employees had been fired or reprimanded for speaking up about safety concerns.

It also came out that a number of experts in the field had voiced concerns. This includes people like Karl Stanley, one of the world’s most experienced submersible engineers. Robert Ballard and James Camron, two of the most respected and experienced deep sea explorers out there, Ballard having discovered the Titanic. James Camron should not be dismissed as just a Hollywood director, as he also has extensive experience in deep sea exploration and has sponsored the construction of his own submersibles for deep sea exploration. Additionally, a number of top technical experts from Trident Submersibles had voiced concerns.

It really seems like everyone who was an actual expert in submersible design and safety, who had seen anything about the submersible had spoken out to someone, often to the company itself, about their concerns. A number of emails have been produced, which prove that the very thing that happened: a catastrophic failure due to depth and pressure.

It also seems that a number of the “partnerships” that Oceangate had touted were, to say the least, trumped up. Was NASA involved? No, not really. Oceangate approached NASA early on about participating in a program, in which NASA experts provide consulting services to private industry innovators. However, they never went very far with this. Likewise, Boeing has distanced itself, saying that they never had any official role in the design of the submersible. It seems that the organization was going it primarily alone, and contact with NASA, Boeing, the Applied Physics Laboratory, at the University of Washington and other professional organizations is that Oceangate has namedropped. Although University of Washington facilities were used to test a model of the submersible, that was the extent of the involvement.

Lack of Certifications and Standards:

One of the biggest things that has come up is the fact that the Titan submersible had none of the major national or international bodies which certify and inspect oceangoing vessels and submersibles. Although this is standard for any legitimate vessel, it was not possible to enforce that requirement on Oceangate due to the circumstances. The Titan submersible was operated primarily in international waters. Testing within US, Canadian and Bahamas waters also were difficult to regulate, for a number of reasons. The testing of a prototype one of a kind submersible is something niche enough that it really does not have comprehensive legislation and caselaw.

Stockton Rush, the CEO of Oceangate, who was killed in the implosion was vocal in his opposition to the requirement for independent certification and classing of the vessel. The general reason for opposing it was that it was too restrictive for such an innovative and nonconventional submersible design. But as a result of this, the submersible not only was fundamentally flawed in design, but it lacked critical safety features like robust communications and fire protection. This is far more than red tape!

It might seem like a burden, but that’s only because the risks are so high. For a design as non-conventional as a cylindrical, carbon fiber submersible, there will be a higher burden than more traditional craft. It would likely have required a large amount of data, from both destructive and nondestructive testing, since the material was unproven in such circumstances. This is an appropriate level of safety and testing for such a hostile environment.

In the interest of keeping this short, here is a list of some of the issues that have come out:

- The titan used only a consumer grade game controller for basic steering

- Lack of redundancy of the thrusters or electrical systems

- Portal was apparently not certified to the depths used

- Interior fittings and equipment did not meet standards for fire and short protection

- Lack of emergency auxiliary life support system

- Inadequate communications, using only a single low bandwidth acoustic modem

- No surface communications such as VHF or satellite

- No GPS, making it impossible to be sure of exact position in an emergency surfacing

- Hatch cannot be opened from the interior and is a laborious process to remove

- Lack of important emergency supplies onboard (First aid kit, fire extinguishers, space blankets)

- “Life support system” based on a plastic bin filled with lithium hydroxide and a computer fan

- Exterior cables and wires not fully secured

- Heavy reliance and faith in an “acoustic monitoring system” for the hull, which was unproven and which experts had stated would likely not provide enough warning to escape a collapse.

These are just some of the major design problems and flaws with the Titan. The overall design of the sub lacked the robust safety and redundancy of previous deep diving submersibles. But above all else, the mentality that seems to have become so pervasive at Oceangate became extremely toxic to good risk management. It appears that they cut corners everywhere they could and had approximately zero oversight.

One thing that is very striking is how ill prepared they were for dealing with a contingency situation. Going to the deep ocean, in an experimental submersible, is obviously a hazardous activity with many unknowns. Typically, there are measures taken to assure that there are ways of responding to an emergency. Things like having an ROV or at least a remote camera to respond to a stuck submersible are standard. There were no rescue resources on standby. They did not even have reliable enough sonar and communications to truly know what had happened.

The thing that is so irresponsible about this is that it ended up placing a huge burden on others to respond at the time the submersible disappeared. Major assets from the US, Canada and from a huge number of private organizations had to be redeployed, with urgency, and at enormous costs. Much of the monetary costs of the loss will end up being absorbed by those who had nothing to do with it.

Carbon Fiber and Construction Methods:

One thing that has been a matter of discussion is the suitable for deep sea use. It’s a material that has not been traditional for submersibles. Carbon fiber is most commonly used in applications that require great tensile strength, but not necessarily compression. There is also the issue of the hull being a cylinder. Although cylindrical hulls are not entirely unusual in submersibles, most of the deepest diving subs use a spherical hull, which is better at distributing the stresses and less prone to weak points. A cylinder requires more careful engineering and potentially stronger, thicker material.

This is not actually an absolute deal killer. Carbon fiber, being a novel material, relatively untested in this circumstance. It does require that a higher burden of testing and a higher factor of safety than well proven materials. In this case, the kinds of measures that should have been taken clearly were not. The carbon fiber may have been sourced from a surplus supply of material which was past its shelflife.

The material also was not tested in the ways one would expect. It was not possible to subject the hull to the full array of inspections and non-destructive testing. It was not possible to easily get sensors to all portions of the hull to inspect it. The rings of carbon fiber cut off of the end of the hull survived. Microscopic inspections has found that there were numerous defects in the hull.

This image, which is part of a series of pictures and videos of the construction of the submersible is quite shocking. It shows workers applying the adhesive that bonds the carbon fiber and titanium rings, which really should have been done in a controlled environment. It seems Stockton Rush himself, and a few others, glued it together in an amazingly amateur manner.

Not withstanding the suitability of carbon fiber for pressure hull at all, there were numerous problems with how it was done in this circumstance. There are too many problems to list, in fact. The hull really should have been made in a controlled environment, such as a clean room and the gluing and bonding o the surfaces should have been done under specialized conditions and possibly in a vacuum.

So what was the technical cause of the implosion?

We may never know conclusively what ratio various factors played in the structural failure. It was certainly a case of standard material fatigue, but there also were problems in the hull at the time of manufacture, such as voids and broken fibers. There is also the issue of seawater infiltration, of the bonding of the carbon fiber to the titanium rings and the fact that titanium and carbon fiber have different coefficients of expansion and compression.

These all seem to have played some role in the failure. What we do know is that a crack seems to have started, toward the front of the vessel, probably around the area where the ring met the carbon fiber. Once the initial crack began, the failure took milliseconds or less to happen. The violence of the implosion meant that death was instantaneous. That’s about the only good news about this event. At least they did not suffer. The hearings, that have dissected the event, have shown that earlier reports that the passengers may have been trying to make an emergency ascent, aware that something was going wrong, but there is no evidence of this.

The images of the debris are very sobering. The failure mode of carbon fiber is much different than metallic materials. When vessels, such as the Scorpion and Thresher imploded, which admittedly happened in shallower depths, the hulls did not shatter into many pieces. In those cases, it usually results in a single weak point, such as a panel or hatch failing, resulting in pressure being equalized. Carbon fiber has no ductility and when it does fail, it tends to be very dramatic.

The implosion has been described as being equivalent to a few sticks of dynamite. What we can see in these images is that most of the hull shattered, and the fact that the failure began at the front is obvious. A portion of the hull is still sticking out and much of the rest has been wadded up into a crumpled mass of carbon fiber and epoxy, shoved into the rear titanium dome. This is where they likely found the “presumed human remains.” Five people shoved into that. There could not have been much left.

Of course, the actual root cause of the tragedy was truly more one of personality, mismanagement, psychology and corporate culture. That is a much more difficult story to work out. What combination of ignorance, recklessness, need for validation, and economic incentives ended up causing this – that will be the story that is retold for years.